Autobiography of Ovid Butler Knapp

August 12, 1849 Queensville, Jennings County, Indiana - June 4, 1929 Battle Creek, Michigan

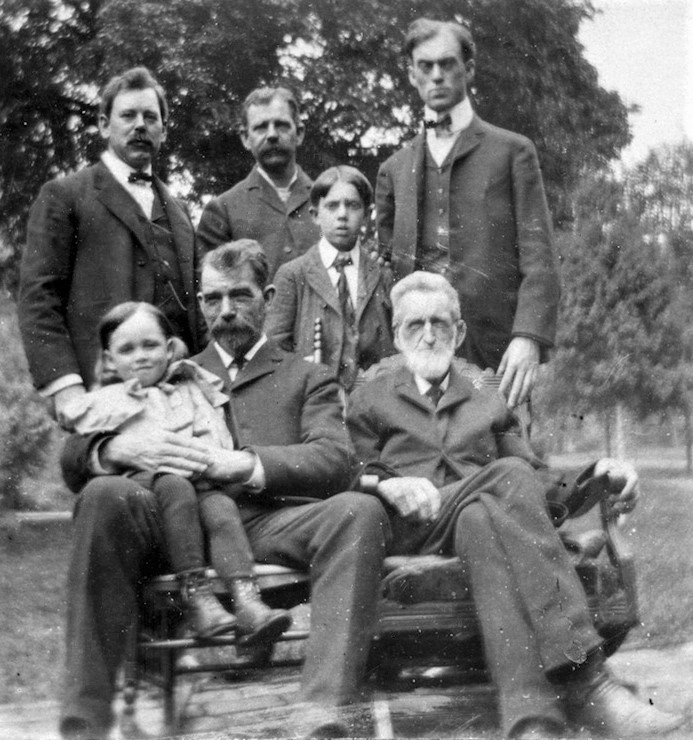

Standing L to R: William Wallace Knapp, Alvin Scott Knapp, Clyde H. Knapp (Alvin's son), Dr. Harry Butler Knapp (Ovid's son). Seated: Franklin Butler Pogue on his grandfather Ovid Butler Knapp's lap. Elijah Washington Knapp, father of Ovid, William and Alvin.

This Autobiography is from the family records held by Richard Schauff of California, and was transcribed by him and posted on the web for public access. Per conversation 6/27/2023 via Ancestry messenger service.

This is January 1929, and I am in my eightieth year. I have had in mind for a long time to write an autobiography of my life, or perhaps it might more properly be called a history of my life's experiences. I am not doing this on account of any desire to raise in the estimation of any who read it, but because it has occurred to me that it would be interesting to some of my grandchildren in years to come to know something of what took place in my life and to note the great advancement in the world that has taken place within my recollection.

I have in my files letters from my grandfather and my father, written more than fifty years ago, which, as time goes on, become more and more interesting to me, and I often read them.

By these memoirs, which I am going to write, I do not mean to intimate that there has been anything in my life but which is common to almost all men. My life's experiences have been very ordinary and have kept pace only with the average man.

I have read somewhere that "There is neither picture nor image of marble, nor sumptuous sepulcher can match the durableness of an eloquent biography, furnished with qualities which it ought to have." To those who read this I will say --- do not look for eloquence or qualities, but for plain statement of facts and of incidents in my life as they may come to my memory.

I was born August 12, 1849, in Queensville, Jennings County, Indiana, a small village in the southern part of Indiana, about 25 miles north of the Ohio river. My father was Elijah Washington Knapp, son of Amos and Polly Butler Knapp. My mother was Sarah Ann (Goodwin) Knapp, daughter of Elijah and Jane Moore (Davis) Goodwin. My father and grandfather, as well as several uncles, were ministers of the Christian church.

My grandfather was known as one of the pioneer itinerant preachers of that Church and was the Editor of their church paper for a number of years. In consequence of the above stated facts my earliest recollections are of preachers and of going to Church. My father's house was always a home for preachers. I was always closely associated with religious people and lived in a religious atmosphere, for which I now sincerely thank the Lord. In fact, had it not been so, it is hard to tell what my life would have been, for, like most men, I am "As prone to do wrong as it is for the sparks to fly upward." And I sometimes feel that I am the weakest of the weak.

Church going and family worship as I remember it in my childhood days was the principal part of our lives. Protracted meetings were frequent. I remember of attending one that lasted more than one hundred days. One man known as "Blue Jeans" Williams did all the preaching in this instance. His texts were all from the book of Revelations. These sermons were afterward published and called "The Voice of the Seven Thunders." (*See footnote.) The appointments for night meetings were always given out for "Early Candle Lighting." The Churches were lighted with candles placed in candlesticks, with a tin reflector behind them. Many additions were made to the church in those meetings.

Frequently the candidates were baptized the same hour of the night, the creek, where the baptizing was done, being but a short distance from the church. Candidates were received into membership after baptism by coming to the front seat and each member of the Church going forward and shaking hands with them during the singing of some familiar hymn. On account of the scarcity of hymn books the preacher frequently read the first two lines and then led in the singing, and after the singing of two lines the congregation waited for the reading of the next two lines and so on through the hymn.

Now, as to the domestic part of my life. I have led a very busy one, not however through choice, for I do not think I was ever very ambitious, but rather through force of circumstances. I was the eldest of the children, and my mother's health not being the best, I was expected to help her and in that way I became quite familiar with housework of all kinds.

My father would always insist upon my first earning whatever money he gave me. He furnished the work and set the price and when the work was done I got my pay. But this did not give me all the money I wanted. I remember one summer after school was out of following, Uncle John M. Brown, as we called him, in the cornfield removing clods from the corn at five cents per day. A day meant from sun up to sun down. The next year I received ten cents per day but had to carry a hoe. From this time until 1872 I followed farming most of the time.

The first political campaign that I remember of was the organization of the Republican Party in 1856, and the struggle between John C. Fremont and James Buchanan, Democratic candidate for the Presidency. It was along about this time that the slave question agitated the whole nation. I remember distinctly of hearing my father read each day of the doings of John Brown, his fight at Osawatomie, Kansas, and his march with his followers through the country to Harper's Ferry, Virginia, where he was captured and finally hung. I remember very vividly of my father reading the account of John Brown's execution and as he read it he and my mother wept, for they were both strong Abolitionists.

This reminds me of an incident that occurred in our village along about this time. As we lived only about 25 miles from the Kentucky line it was quite a frequent occurrence for slaves to run away and many of them came to our town. Near town there was a Negro by the name of Madison Smith who owned his own farm. These runaway slaves would go to his underground railroad to hide. This was along about the time of what is known as the Dread Scott decision by the Superior Court regarding the return of runaway slaves. Two slaves had run away and were hiding at Smith's place. Their master came after them and found them and brought them into town where he got a couple of trace chains (these chains were about six feet long, with a ring at one end). He had our blacksmith make handcuffs, one for the right, and one for the left wrists. After riveting the chains to the cuffs he riveted the cuffs to the wrists of each negro, mounted his horse, and placing one on one side, and the other on the other, putting the rings of the chains over the horn of his saddle and rode off down the road towards his old Kentucky home at a brisk trot. The last I can remember of them was seeing those darkies on the run being almost dragged along. It is needless to say that this forever confirmed my already strong feeling against the slave question.

As I remember it was along about this time that the Lincoln and Douglas debate was published and also it was about this time that I got hold of Harriet Beecher Stowe's "Uncle Tom's Cabin". This book at that time was considered almost sacred by all Abolitionists and made a very profound impression upon the minds of all who read it. I consider this book as the foremost and leading cause of the final abolition of slavery.

Those were certainly stirring days in the history of our great nation as well as in my own experience. Leading as it did up to the political struggle between Lincoln and Buchanan and the first triumph of the Republican Party, which shortly lead up to the "Civil War". It did not at the time, to me, seem very civil and I do not think it was called civil until after it was all over.

Living so close to the Mason Dixon line I presume we saw in our neighborhood more of the real hatred manifested between the union people and the rebel sympathizers, than was seen farther north. Quarrels and fistfights were common, although I do not remember any of our lives being taken.

I remember well, it seems but yesterday, that day that Fort Sumter was fired on. My father had been down in town and a telegram had been received giving the news. Father came home to tell us. I was hoeing in the garden and he came to me and said, "The war has commenced. Ft. Sumter was fired on last night." I stopped and listened expecting that might be able to hear the roar of the cannons. I was about eleven years of age at that time.

It was soon after this that Lincoln made his first call for one hundred thousand, three-months soldiers. I never can forget the thrill that I experiences as a crowd would gather under the stirring music of the fife and drums with "Old Glory" waving proudly over our heads, and some speaker would mount a dry-goods box and deliver an oration on the cause of the war, winding up by calling for volunteers. The boys and the old men too, would crowd up to see who could get their names down first. It was but a short time until troops began to gather here and there in camps, and officers from the regular army were sent out to drill them and teach them the art of war. Young people nowadays talk about getting a "Thrill". If they had lived in those days and seen what I have seen and gone through what I and all the others at that time experienced they would have thrills enough to last a lifetime. Even now when I see a company of soldiers and hear the shrill notes of the fife and the rat-a-tat-tat of the snare drum and the boom of the base drum I acknowledge I still get a thrill and I wonder whether it is a thrill or a feeling of patriotism. It does not seem possible to me that a person living through those days north of the Mason and Dixon line could be anything but patriotic. I remember of reading one of Horace Greeley's speeches, when he was candidate for President, in which he made the remark that all Democrats are not horse thieves but all horse thieves were Democrats. So I say that during the Civil War days all democrats were not rebels but all rebels were democrats.

It might be interesting to know that at the time of the Civil War there still remained many of the old soldiers of the war of 1838. And I heard of some of the Revolutionary soldiers living but do not remember that I ever saw one. But in our there was a warehouse stored full of the old flint-lock guns left over from the revolutionary war which the government took and made over into muskets for our soldiers. It occurs to me just now that a remark concerning President Lincoln's first call for troops for only three months might be in order as the propriety of such a call has been questioned. After a close study of this I am sure that Mr. Lincoln was right. Had it not been for the fact that England furnished boats for the blockade, guns and ammunition for their soldiers and money to finance the war against the union, the war would not have lasted three months. Then to think that they have had the cheek to ask us to pay the Confederate war debt is certainly the limit. But this is the kind of friend we always have had in England and it will never be any better except when they got in such a mess as they did in the World War and need our help to get them out of it. England today would have been German territory but for Uncle Sam's help.

I remember well all the principal battles of the Civil War and especially the battle of Gettysburg. As the history of the Civil War is known to all I will only mention few of my experiences. I well remember the time of Morgan raid, in Indiana, which occurred the latter part of June 1863. We had no warning of this raid and did not know he was in the State until he was within a few miles of Vernon, our County seat. I was plowing corn a few miles from there when I received word that Morgan was coming. I remember I stopped my horse in a row of corn, tied the lines to the plow and ran for home. I suppose I went back and got the horse but cannot remember how long I left him there. This was on a Saturday morning. Immediately preparations began for the expected battle, which never occurred. All valuables were hid. Doors and windows of all public buildings were boarded up. Women met to prepare cotton bandages and lints for the wounded.

I remember one incident that happened that day. An old man who was a strong sympathizer with the rebels went into a place where these women were busy with their work and inquired what they were doing and when told he made some slighting remark which offended the ladies. A number of us boys were standing around and one of the women turned to us and said, "Hang the rebel." Some of us got a rope and I expect we would have executed the sentence had we not been stopped by older heads.

Preparations went steadily on all that day. About dark we were told of a few guns and some ammunition that a farmer had, who lived about two miles from town. It was nearly in the direction from which we expected the rebels. I was selected as the one to go and get them. The night was very dark but I mounted my horse and started. I rode very slowly so as to make as little noise as possible for fear of running into the rebels. I arrived there safely and got the guns and ammunition, but on the road back into town there was a little stretch of hard road and the people hearing the clatter imagined the whole rebel cavalry was right after them. When I reached town it seemed to me as if there was a prayer meeting being held on every corner.

The next event of importance that stands out on my memory was the assassination of President Lincoln. These were the darkest days of the war. Many thought the war had been a failure and the union cause was lost. I verily believe that God raised Lincoln up for just such a time as that, and looking at it from a human standpoint, it would seem that his death came just at the wrong time. This reminds me of the speech made in Chicago by James A. Garfield on April 25, 1865. A crowd had gathered in front of his hotel early in the morning and they called for a speech. He commenced by saying, "The God of Heaven still reigns. Justice and judgment are the habitation of His throne. Mercy and truth shall go before thy face and the government at Washington still lives." It was just such courageous words as these, spoken by brave hearts that in the providence of God saved the Union. Perhaps he wished to teach us that no man could save the Nation and to have us remember that He had said, "Blessed is the Nation who's God is the Lord." And again "That the living may know that the Most High ruleth in the Kingdom of Men and giveth it to whomsoever He will".

That April morning after Lincoln's assassination I will never forget. There had been some rain and wind during the night and before starting to school my father said we had better go over the pasture fences to see if they had blown down. The fence was along the railroad track and while we were there an early passenger train passed and we noticed the engine and coaches were all draped in black crepe. My father remarked that he presumed that some of the officials of the road must be dead. Soon after this a lady who lived on the farm just above us, who had been to town came walking up the track. She called to us and asked if we had heard the news. Father replied that we had not. (He had a nail in his hands just ready to put it on the fence) and when she said that Lincoln was assassinated last night, father dropped the nail and sat down on the ground and cried like a child. Presently he got up and said, "Let's go home". I went on to school and when singing and prayer, as was customary opened school, the teacher made some remarks upon Mr. Lincoln's death and many tears were shed. The rest of the day the school was as quiet almost as if the corpse was lying in our schoolroom, and the talking was done in whispers. When Mr. Lincoln's body was removed from Washington to Springfield they stopped over a part of one day at the Indianapolis and it was my privilege to see him as he lay in state in the Capital building. I will state that same time before this I saw John Wilkes Booth, Lincoln's assassin, playing in "Ten Nights in the Bar Room" at a theater in Indianapolis.

I was too young to go into the army, but just before the close of the war I volunteered, but on account of my age and slender build I was rejected. I was afraid to ask permission of my parents to go for fear they would object, so I ran away from home to enlist. I had always prided not to do anything that my parents told me not to do and this was my reason for going away without asking.

The summer and winter of 1866 and 1867 I attended school at State Line City, Indiana. In the fall of 1867 I went to Missouri with my father intending to remain there with an Uncle for a while. After we were there a short time we learned that the people in that state hardly realized that the war was over and it did not seem to be very healthy for Union people, so we returned to Indiana. However early in the spring of 1869 I again returned to Pleasant Hill, Missouri and worked on the farm for a cousin, David Chandler, for a short time. Then I worked for Elhanan and Hiram Todd. (Brothers)

During this summer two young men and myself took a trip into Kansas with a team and wagon. This was before there were any railroads in Kansas, and it was very wild country. It was on this trip that I saw Indians for the first time. Our introduction to them was a little startling to say the least. One noon we came to a nice grassy place on a creek and stopped for lunch and to feed our team. Just as we were ready to eat, all of a sudden a lot of Indians jumped up out of the grass. It being my first sight of Indians I supposed our time had come. I had a gun in the wagon and I jumped up and grabbed it supposing we had to fight for our lives. But the boys with me, who had had experience with Indians and told me to put my gun down and come out of the wagon, which I did. The Indians came up and laughed at me. They remained a short time and then left quietly. It was on this trip that I came the nearest of losing my life that I ever did. As we were driving along we noticed some prairie chickens in the road ahead of us. We stopped and I got out and went to the rear of the wagon for my gun. In pulling it out the hammer caught on a board and it went off. The shot just missed my head going through the rim and crown of my hat and knocking me down as quickly as if it had gone through my head. However I got up and with the other barrel got the chickens just the same.

About the first of December 1869 I returned to my father's at Queensville, Indiana and remained until March 16th, 1870, when I was married to Miss Jennie McNeal at North Madison, Indiana by Rev. W. W. Monroe, pastor of the Baptist Church at that time. We returned to Queensville the next day, and in a day or so went to keeping house for ourselves in a log house on a farm near my father's farm. I had expected to run my father's farm but we could not agree on terms. A number of friends were immigrating to Minnesota that spring so we decided to go with them. There were twenty-one men, women and children, six covered wagons and fourteen horses. We left the 15th day of May and arrived in Meeker County, Minnesota, June 28, 1870. We found a very new country. Work was scarce, and as our means were very limited, we soon learned what frontier life meant. I finally hired out to a farmer, but had to wait until after harvest and threshing for my pay. Soon after harvest I hired out with my team to help run a threshing machine at fifty dollars per month. From the two jobs we saved money and we rented some rooms in a house in Litchfield, Minnesota where we lived until about harvest time 1871. Our first child Katie May was born January 9, 1871.

The summer of 1871 I took a contract breaking 160 acres of prairie land on Round Lake, about 3 miles south of Litchfield, and also rented 160 acres of broken adjoining that, which I put into wheat and oats. The winters of 1870 and 1871 were very hard winters and certainly made it very hard for us to pay our way. We were determined not to go in debt. My father was amply able to help us but I did not care to ask him for help because before leaving home I had asked him for a few dollars and he refused, saying to me "give a hog corn and he will not root." So we rooted and those two winters were certainly hard rooting for the only thing I could do was to take my team and go to the woods, which were some ten miles away and cut a load of pole wood and haul it home. This I would do three or four days each week and often it was forty degrees below zero. When I had gotten quite a pile of the wood I would stop hauling for a few days and saw and split my wood into stove lengths and then I sold it around town. Thus we managed to live. The farming venture did not prove very profitable, as wheat was about seventy-five cents and oats ten cents per bushel.

In the meantime our folks had moved from Indiana to Pleasant Hill, Missouri, and they thought that we had better come there, so in October of that year we started for Missouri. It was the very day of the great Chicago fire. We went all the way from St. Paul to Kansas City by boat. It took about a week to make the trip owing to the fact that the rivers were low. This was one of the most enjoyable trips of my life. Our daughter Katie was about nine months old and could say "papa and mama", and we thought her to be a most wonderful child, and it seemed that all passengers thought so too. On our arrival at Pleasant Hill, the next move was to find something to do because money was still scarce. At this time I ran across an advertisement of a telegraph school in St. Louis, and at once decided to learn telegraphy. I went to St. Louis and entered McEachern's telegraph school and remained there a number of months or until my money ran out. I had to learn to take about 25 words a minute, which at that time was the standard. I applied for a position in East St. Louis on the Vandalia Railroad. This was night work. As soon as I reported in the evening the day man immediately left and I found myself alone with about a half dozen sets of instruments to look after. I soon found that the sound of the instruments on main lines were quite different from an institute line. The circuits were short and I found myself unable to get even a call. So when I discovered what a mess I had gotten into I lost no time in closing the office and taking the key to the hotel where the day operator lived, and then getting out of sight as soon as possible. I never again told anyone that I was an operator until I had gained practical Railroad experience.

While in Minnesota I became acquainted with J. W. Glassford, the Agent and Operator for the old St. Paul and Pacific Railroad at Darwin, Minnesota, a small town 6 miles east of Litchfield, where I had previously lived. As I realized now that I must get railroad experience before I could hope for employment along this line I wrote Mr. Glassford, and asked for the privilege of coming to his office to learn railroading and get some practice in telegraphy and bookkeeping, the latter of which I literally knew nothing. He at once wrote me if I would come out and buy his house and lot that he would teach me the business and give me the station, but I must be ready to take charge by September 1st, 1872. This gave me little less than two months time to learn all that was necessary. I went at it with all my might and worked almost day and night and was ready in a way. I took charge of the work at the stated time.

When I look back and see how inefficient and awkward I was in that kind of work I marvel that the company ever put up with me. I presume it was on account of the scarcity of men to do such work. However I managed to hold it down for eight years without a single days vacation. During these eight years I worked almost night and day, for mind you, I was not only agent and operator for the railroad company, but I was Postmaster and grain elevator agent. I also sold lumber and feed as well as filling the office of Justice of the Peace, and as a sideline ran a 160 acre farm, and I went out into the county, Sundays, and often evenings and conducted religious meetings when there were no preachers available. Preachers and Churches were scarce in those days and the meetings were usually held in private homes or schoolhouses whenever possible. This work finally led up to holding evangelistic meetings in different places, which I did evenings, and by the blessing of God met with some success. While I never had any regular charge, yet I was kept quite busy for a number of years. All this time I was working for the railroad company. For fear that some might get the idea that I did this to get more money I will state, that in all my experiences in holding meetings I never accepted one cent of money. I had been ordained by the Christian Church but worked with different Churches.

At one time while agent at Milaca, Minnesota I conducted services for the Methodist people for three months while the pastor was sick.

I worked thirty-eight years and three months for the railroad company. I went to work September 1st, 1872 and worked most of the time until I lost my arm, May 12th, 1914. I was stationed regularly at Darwin, Litchfield, Dassel and Milaca. I worked as relief agent at Long Lake, Maple Plain, Delano, Montrose, Howard Lake, Smith lake, Grove City, Atwater, Kandiyohi, Kerkhoven, Hancock, Campbell, Breckenridge and Havana, all on the Breckenridge division, of what is now known as the Great Northern Railroad. I also worked at Thief River Falls, Erskine, Warren, Stephen and a few other stations on the Crookston Division. When I first began to work for this company it was known as the St. Paul and Pacific, later the St. Paul, Minneapolis and Manitoba Railroad, and now the Great Northern Railroad.

Many of my experiences during these long years would no doubt be interesting, but I shall mention but a few. In the early days of my railroad experience I cannot conceive of what station men and operators now would think if they had to put in the long hours and do the work that was expected of us then. It was a daily occurrence to have to put in twelve to eighteen hours per day, and no allowance for extra time. The wages were so much per month with no limit in hours. In case of accidents, storms and snow blockades, in the one-man stations, our time was only limited to the time it took to get trains on regular schedule. I remember at one time remaining on duty for 36 consecutive hours. We did all our own janitor work and in addition, our switch lamps had to be cared for which required that they be brought in and taken out daily. This of course was in addition to all our routine office work and Western Union Telegraph work.

I now know of some stations where they have three or four men to do the work, which I did alone, and at present the section men now care for switch lamps. Today every man gets better wages than we did in those days - and too, these men are continually asking for more pay, while such a thing as asking for more pay never entered our minds.

I have never had the advantages of many of the so-called worldly pleasures. My recreation has consisted mostly of hard work and of helping others, and I can truly say that I have enjoyed it and I believe far more than those who have plunged deep in the so-called recreations of the present time.

I am thinking now of some of my boyhood experiences. I remember that during the Civil War that we boys formed a club, if you please, and our duty and pleasure too, was to go around to the war widows (wives of soldiers that were in the army) woodpiles, after dark, and saw and split up their wood and often carry it in and sometimes receive a lunch for our trouble. I tell you it was real fun, fun that we got lasting enjoyment out of, the thrill of which often comes to me even yet. I do not believe there is any greater pleasure than doing a kindness to others. This feeling in me makes me understand plainly why our Savior said, "It is more blessed to give than receive" and in fact is it not this spirit of giving that caused Him to give his life for us?

I remember a cold stormy night in Minnesota while we lived at Darwin, the thermometer stood between 30 and 40 degrees below zero. A widow with three children lived in the woods some three miles from us. We knew they were very poor and needy. I had just gone to bed and my wife remarked that she wondered how poor Mrs. Ferguson and her children were on such a night as this. I jumped out of bed and began to dress and I said that I was going to know how Mrs. Ferguson was before I went to sleep.

"Are you going out there tonight?" my wife said. "Yes", I said. "Well, I am going with you!" was her reply. I went to the barn and hitched my horse to the cutter, drove to the house. We took along some flour, a jug of buttermilk and a chunk of meat as we left our comfortable home. A more pitiable sight of human wretchedness I think I never saw…they had no stove, only a small fireplace with very little fire and no wood to speak of. I went out, and after some time succeeded in gathering up a few armloads of wood out of the snow, which was about two feet deep, and brought it in and soon had a good fire going. My wife fixed them up a very good meal, and we soon had them warm and quite comfortable, and considerably cheered. There were two hearts that were rejoicing and at least inwardly praising God. Remember that our Savior said, " In as much as ye have done it to the least of my brethren you have did it unto me." The next day was Sunday and I went out among the neighbors and got a few teams and before night we hauled up enough wood at the widow's house to last the rest of the winter. And the next night we sure had a good rest both mentally and physically.

My father's manner of punishment for us children was different from any other person I ever knew. I am relating it on account of its unusualness. I presume we children were as human as any others. At least I know I was, if not a little more so. When we did anything for which we deserved punishment it was apparently forgotten, but in a few days, perhaps a week after it occurred father would say, if I was the offender, "Butler, I wish to see you in the other room". When we were alone, he would rehearse the whole matter and show us our wrong and then kneel and pray with and for us. I ask, "Did you ever know any father to punish his children in such a way?" As you no doubt have heard, the principal part of one's education in the early days was the three "R's": "Readin', 'Ritin', 'Rithmatic", but I was reading the other day that it had been changed to the three "C's": "Character, Culture and Citizenship," and it seems to me that this is a most excellent change, because it not only includes the three "R's" but very much more. I well remember my experience in learning arithmetic. Slate and pencils were scarce articles, so my father told me I must master first and second parts of arithmetic mentally before I could have a slate and pencil. I was so very anxious about this that I would study late in the evening and then get up about 4 A.M. and stir up the fire in the large fireplace; lay down in front of it with my book and study. By spring I could do any example in the two books mentally. This I considered the best mental training I ever had.

Some experiences in more recent years may be interesting. I was always interested in temperance work and did all I could against saloons and intemperance in every form. At one time while living in Dassel a fight was on between the temperance people and the saloons. It happened that I was candidate for Councilman. The result of the vote was a very peculiar one. There were three majorities in the general vote for the saloons, while there were three temperance men and two saloon men elected on the Council. Nearly every one took the position that because of the majority for the saloons we would be compelled to grant the saloons a license. I contended that it was optional with the Council regardless of the majority vote, and it was finally decided to set the license fee so high that no one would apply for them. I told them that I would not vote for license at any price. I spite of me they voted a $5000 license, fully expecting there would be no applications, but before our next meeting we had two applications for license. In the meantime I had referred my contention that we did not have to grant license, to the State's Attorney for his decision. He decided that this was right and when the vote was taken the deciding vote fell to me for there were two for and two against it.

When the saloon keepers and their allies found they were blocked on account of my vote, they at once got busy with a petition to the railroad company to have me removed as agent of the railroad station. In a few days the division superintendent came down with his car and came into my office and said, "I understand you were elected as one of the Councilmen in the village."

I replied, "Yes, I was".

"I understand too that it was your vote that put the saloons out of business".

"Yes, I guess that is correct".

"Well", he said, "You will have either to resign from your office on the Council or as agent for the railroad company".

"You have my resignation as agent", was my reply.

He seemed very much surprised and replied, "You can't make a living as Councilman, can you?"

"No, there is nothing in it, but every vote that was cast for me was a vote against saloons. If I should resign as Councilman this would open the saloons again, and I will not deceive my friends."

He went over town and was gone two or three hours, when he came in again and said to me, "I have been around and I find that your opponents are all saloon men and their friends, which are mostly old soaks. You are right, so you can remain as agent."

To illustrate the practical working of the temperance principal I will relate an experience I once had. I had been working some months as relief agent at Thief River Falls, Minnesota, and about the time I was relieved a friend came in and wanted me to accompany him some forty or fifty miles to look over some government homesteads. We drove out some twenty-five miles and came to a stretch of low level land all covered with water, as there had been very hard rain the day before. It was impossible to drive across it. There being a homesteader living near, we decided to leave our team and wade to the other side, some ten or twelve miles. The water was from ankle to almost knee deep. It was nearly dark when we got to the other side. We finally found a homesteader where we remained overnight and dried ourselves. We were pretty stiff and sore the next day, but we tramped around looking at lands, then about 4 o'clock we started to wade back. We finally reached our destination some time after dark. Just before reaching there my friend remarked that he wished he had some whiskey and if the man where we were going had any he would buy it. When we got in we found he had a pint and we bought it.

I said to my friend, "I will take half of it. What are you going to do with yours?"

"Why, drink it, of course!" he replied.

"Well, you can drink yours, but I will rub mine in". And so I did. The next morning he was so stiff he could scarcely walk while I was as supple as I ever was, and never felt better. This represents the only benefit there is in the use of whiskey, in most cases.

Now about all that is left for me to relate is the wonderful improvements, inventions and increase in knowledge, that has taken place within my recollection. The telegraph of course had been invented, perhaps a few years before I can remember, but telegraph offices were very few and far between. I remember well the first one I ever saw. I remember how I stood looking through the window in wonder and amazement at the operator copying messages. Little did I think at that time that I would or could ever learn it and would do the same thing for more than thirty years? The instruments in those days were crude affairs compared to those of the present days. In fact, many of them were what were known as "Tape Machines" or "Registers". They were machines through which a paper tape was ran by a clock-like machine, operated by weights or springs, and which had to be wound up like a clock. This was kept running while a message was being received. On the end of the armature of what was called the sounder was a needle that made dots and dashes on the tape and the message was read from the tape. That you may know something of how it looked, I am writing my name:

O B K n a p p

... / -... / -.- / -. / .- / .--. / .--.

It is quite fascinating work. By long practice one almost becomes a part of the machine himself. That you may know what I mean by this statement I will say that I have often copied messages while someone was talking to me on while thinking of something else and when I was through I would have to read them to see what I had copied. The most singular feeling I have had in this work was when I copied from the wire the announcement of the death of one of my own brothers, and then a few years later a message telling of the death of my father. These messages were not wholly unexpected but gave me a peculiar sensation, nevertheless, in taking them off the wire myself.

I think I was acquainted with a man who invented the electric light before Mr. Edison did. He was an operator at Dassel, Minnesota and his name was George Breed. It was sometime in the summer of 1873 that I visited him and he showed me what he had found. He had whittled out of charred wood a couple of pencil-shaped carbons very similar to what is used today, and attached copper wire to each of them. The other ends were attached to homemade batteries. He held the two ends together and produced a light, and remarked to me, "Someday this whole country will be lighted in this way." However it seems that it remained for Mr. Thomas A. Edison to re-invent it and put it in shape to be used as it is today. What an opportunity was knocking at Mr. Breeds door but he knew it not, and so far as I was concerned I hardly gave it a thought until I began to see electric lights shining all about us.

I remember well the first sewing machine I ever saw. It was a "Howe" and was a small affair that was set on a table and turned by one hand while the work was guided by the other hand. It made a chain stitch and sometimes an end of a seam of some thread would get caught and ravel a whole seam out, and some very amusing things would happen on account of it. Just imagine the seam in a pant leg pulling out from top to bottom while walking on the street. Such things did happen.

Farm machinery was very scarce and but few farmers could afford to buy it. The first mower I ever undertook to run required four horses to pull it, and then I had to rush them in order to get up motion enough to keep it from clogging. Threshing machines were indeed few and far between. The flail was the most prevalent, but many of us who had barns laid the sheaves of wheat heads on the floors, and tramped it out with horses. Many a day I have ridden some old horse or driven a span of colts over the straw until all the grain was tramped out of it. Then we forked the straw out and gathered the grain in a heap in a corner finally running it through a fanning mill to clean it up for milling.

But with the coming of the modern self binder, the thresher, and the power machines of this day there has come about a heavy production of farm products, and as the result of low prices, thousands of farmers have been starved off the farm and are now being absorbed into the great cities where the great industries offer year-round employment. The vast developed and production of farms run on a large scale and using power machinery is changing the face of the earth, and where once the honest hardworking farmer with his 80 or 160 acres could raise and educate his family and have money in the bank, today he is playing a losing game. Until this adjustment between the farmer and the city men is completed the small farm owner is bound to have his troubles. I think it was Senator Louden of Illinois who said that today the farmer is paying 70% more for what he has to buy in the form of machinery and tools and materials with which to run his farm, while in fact he is only receiving 40% more for what he has to sell than he got before the late war.

My railroad experience came to an abrupt end on May 12th, 1914. One of the many duties, which my position as station agent carried, was that of giving attention to a pumping station maintained by the Railroad Company for the pumping of water for the engines. When the level of the water got low in the tank it was necessary to start the pumps and bring the water level up.

The last duty I performed after 38 years of railroad service was to walk down the track nearly a half a mile to the pump house, and start the large gasoline motor that pumped the soft cool water from Spring Lake up to the water tank near the station. I had just started the motor, which was a large single cylinder affair with a heavy crankshaft, and was oiling the gear and the bearings, when my coat became caught in the revolving shaft. I immediately braced myself with my right hand against the fender or guard which covered the crank of the motor and was able to hold on till my coat was ripped off, but just as it gave way my hand slipped and went full length into the fast revolving motor crank, with the result that before I knew it my hand and forearm was off at the elbow. Seeing my hand drop to the floor across the room revealed my first knowledge of what had happened. To be alone and nearly a half a mile from help with an arm off put me in a bad plight, but presence of mind told me to place my left hand over the bleeding arm and hold it tight and walk as fast as I could toward the doctor's office. I was given first aid by the doctor and taken to Litchfield to the Hospital where the amputation was cared for.

One never realizes how many friends from near and far one has until a calamity like this befalls. I was the recipient of dozens of letters and telegrams and can never forget the most generous expressions of sympathy, which came to me from people whom I least expected. These expressions, so generously received, were most helpful and made the loss of my trusted right arm less hard to bear. For a man 65 years old to lose the only right arm he had and to learn to write left-handed, offered quite a problem. After a settlement with the Railroad Company I knew that my work as railroad station agent had ended. Having lived in the region of a good farming country, and with training early in life to till the soil, my thoughts naturally drifted toward agriculture, and for several years following the loss of my arm I cultivated a 30-acre farm, two miles east of Dassel, as well as cultivated my health. Although never sick the open life of exercise, fresh air and sunshine hardened my muscles, and I really enjoyed the toil and labor incident to this work. How I accomplished what I did on this farm with only one hand is more than I can realize, but the Lord helps those who help themselves.

* (Note: Ovid may rather have seen Joseph Lemuel Martin, preacher and author of "The Voice of the Seven Thunders." "Blue Jeans" Williams was the nickname of James D. Williams, politician and Governor of Indiana from 1877 - 1880. Williams was not a preacher; perhaps Ovid saw him come to town and make a speech?)

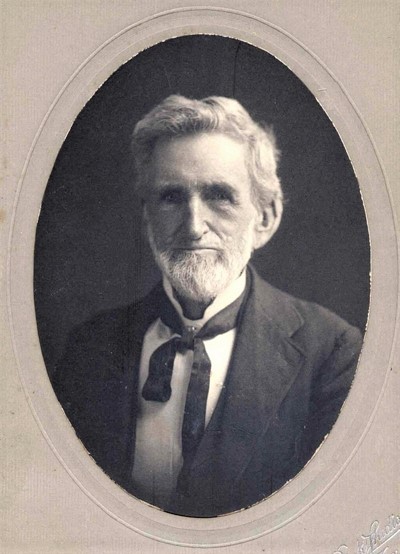

Parents of Ovid Butler Knapp

Sarah (Goodwin) Knapp & Elijah W. Knapp

Sarah (Goodwin) Knapp & Elijah W. Knapp

|

|

Elijah W. Knapp Buried

Funeral of a Man Who Did Much to Establish Butler College

The funeral of the Rev. Elijah W. Knapp was held at 2 o'clock this afternoon from his late residence, 336 Burgess avenue, Irvington. Mr. Knapp was one of the oldest residents of Irvington, having lived there since 1876. He was one of the first drawn to the suburb by the advantages of Butler College.

Since its earliest conception Mr. Knapp was identified with the interests of the college. He spent several years traveling throughout the State, interesting the membership of the then struggling organizations of the Disciples in the proposition to establish a college, and the final successful launching of the venture in the late 50s was largely due to his efforts. The college was first located in Indianapolis and called the Northwestern Christian University.

While yet young his religious instinct drew him into active church work. He was one of those to come from southern Indiana to Indianapolis in 1839 to attend the first State convention of the Disciples. For many years he was recognized as one of the most earnest preachers of that denomination. His efforts were particularly effective in weak and disorganized congregations and in elevating the spiritual and moral tone of those within his influence, both from the pulpit and in his daily association.

He leaves surviving him a widow, who is a daughter of the late Rev. Elijah Goodwin, and five children, O.B. Knapp of Dassel, Minn; F.C. Knapp, of Acampo, Cal, and A. S. and W. W. Knapp and Mrs. Laura Weaver, of this city. The funeral services were in charge of the Rev. F. C. Norton, assisted by the Rev. A. R. Benton. MRS. SARAH KNAPP DEAD

Aided in Establishing University in Irvington

Sarah A. Knapp, age eighty-three, widow of Elijah W. Knapp, died at her home, 304 Burgess avenue, Irvington, late yesterday afternoon. She was a daughter of Elder Elijah Goodwin, one of the pioneer preachers of the Christian church, who was pastor of the Central Christian church of this city in the early sixties.

The early years of Mrs. Knapp's married life were spent at Queensville, in Jennings county. Her husband was a minister. He was active in church organization work. They were instrumental in establishing the old Northwestern Christian university, now Butler college. They moved to Irvington in 1876, chiefly because of the location there of the college.

She is survived by three sons-Ovid B. Knapp, of Dassel, Minn.; A. B. Knapp and W. W. Knapp, of this city, and one daughter, Mrs. L. M. Weaver, who lived at the family home.

The funeral will be held at the home at 2:30, Sunday afternoon.

You may use this material for your own personal research, however it may not be used for commercial publications without express written consent of the contributor, INGenWeb, and